Week 11 – in which I try to be honest about the appeal of AI, identify some problems, and decide exactly where we stand

Current attitudes to AI seem to fall into four main categories1: those who love it, those who hate it, those who just use it, and those who just don’t. Your grandad is probably in the last category, or your mother-in-law; they have no ideological antipathy toward it, they just find it confusing and unnecessary.

Of those who just use it, their reasons are similarly non-ideological. Who cares about the ethics of it? As long as they can get a reliable recipe for tagliatelle carbonara, or instructions on how to get grass stains out of jeans, then they’re happy. Of course, bog-standard websites can also provide you with this information, just not as instantly or handily. With AI, you don’t have to wade through twenty different recipes to find just the one that doesn’t use mushrooms; you can just say, “Adapt that recipe so that it doesn’t use mushrooms”, or “make it vegan” (or whatever). In other words – and this I think is the future of web search, whether we like it or not – it allows you to interrogate knowledge, to customise it. And even the Luddite in me can’t help but think that this is pretty cool. We’ll come back to this very telling word customise later on, but for now let’s press on with the remaining two categories.

Next are the evangelists; they don’t just find it handy, they think it should be used by everyone for everything. Admittedly, some of these are people who have a vested interested in broadscale AI adoption (e.g. those selling AI services, tech entrepreneurs and social media barons), but this subset also includes professional people who have incorporated AI into their workflow. And here we find not a few authors, illustrators, designers, and publishers. The rationale for this seems to be, “Well, it’s happening anyway, and if I don’t get on board, then I’ll be left behind and lose out on work.” This is just a very understandable response to the old dilemma: evolve or die? And I get it: I did this myself in making the move from traditional to digital drawing some years ago. AI can definitely speed things up, and faster usually means cheaper, so if you’re a freelancer wondering how you’re going to do such aspirational things as pay the rent or eat, then the “not dying” option can seem very tempting.

And finally, there are the people who hate it. They don’t just have no use for it, they loathe the very concept of it. Full disclosure: I am of this camp. Well, I don’t loathe it. As a technology, I am hugely impressed and occasionally gob-smacked by its capabilities, whether that be in words, images or sounds. And – more full disclosure – I have used it occasionally. Not usually to create anything (unless I’m just curious and fucking around), but to check facts, explore subjects, think through options, etc. And in this it is very useful – or at least, it would be if its answers could be trusted, because ultimately it ends up costing me more time as I have to then hunt down reliable resources with which to cross-check what it’s said. True, the better AIs are now more transparent about sources, and so this reliability problem is perhaps lessening, but it’s still a huge worry how many people are relying on AI for important information. I give you: Exhibit A!

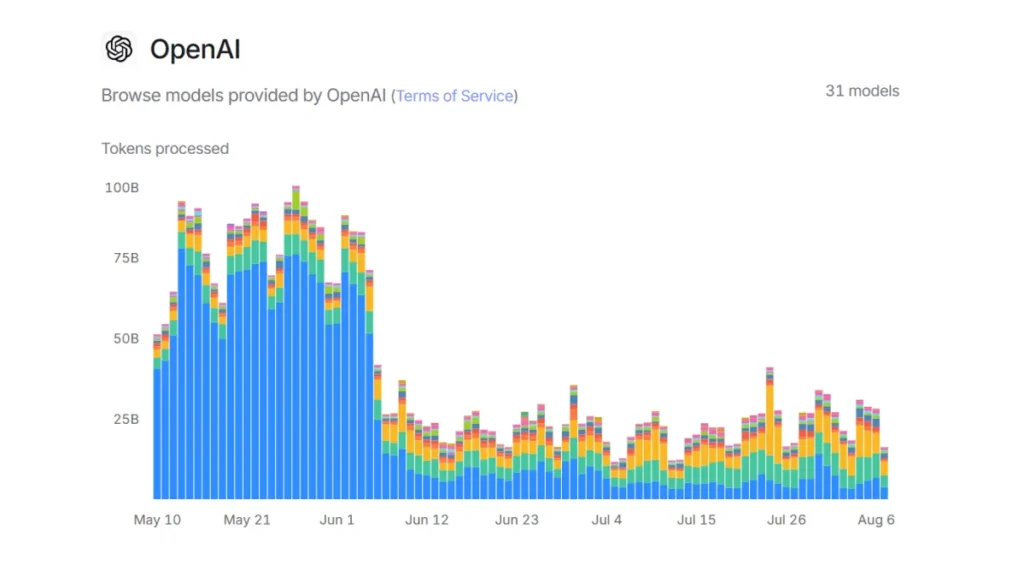

This darkly hilarious graph represents ChatGPT use just as schoolkids and students break up for the summer (you can practically see the point where the final bell rings for the holidays!). Oh dear. What are we preparing our youth for? PhDs in Prompt Writing?

So, aside from the errors, the flat out lies and the hallucinations – let’s call that “Problem 1” – the other major downside of AI is deskilling and cognitive decline (“Problem 2”). Media theorist and cultural critic Marshall McLuhan wrote:

“The wheel is an extension of the foot. The automobile is an extension of the foot. The bicycle is an extension of the leg.”2

Through technology, McLuhan envisaged the extension of the human body, as if the electrical wires looping from pylon to pylon were the nervous system of an ever-expanding self. Which all sounds great(?), but we should also remember that the foot that cycles or drives doesn’t walk. And when we extend this to thinking, and reading, and just about anything that involves cognitive work, then we quickly begin to see the danger: AI will make us intellectually unfit.

In his private diaries, the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “Every day I begin with hope, and every day I end in despair.” If only he’d had ChatGPT! Thomas Edison wrote, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” Think what elbow grease he’d have saved himself it only he’d had Gemini or Claude! But any artist, thinker, writer or creator will recognise these sentiments. Creation is necessarily hard. True, ideas can also come easily, or out of the blue. Mozart once famously said, “I write music how a cow pisses”. But most of us are not so gifted, and creative ideas often appear at the end of an intense period of struggle and reflection. And – as Edison points out – the idea itself is only a tiny percentage of the battle.3 The main struggle is with the realisation: honing the craft, developing our skills, problem solving, constructing, refining, polishing. I think this is why Stephen King hates James Patterson (and why he probably hates AI), and why I hate most conceptual art: creating something is a craft, it is work, and it is through this process that we refine and discover and evolve. The idea behind that process is actually a lot less important. And if we (and our children) no longer experience this process, then how can we value what we “create”? How can the fledgling writers, artists, musicians of tomorrow acquire knowledge and mastery of the tools at the necessary level of detail? At the level of word, note, and brush stroke? How can they be anything other than “directors” or “prompters” and “visionists”?

Thanks for reading Diary of a Micro Press! Subscribe to keep up to date with publishing-related news, tips, offers and opportunities, and the ongoing adventures of running an independent micro-press.

Problem 3 is ethics, or more specifically, “the Big Steal” (as I’ve decided to call it). I mean, call it what you want, dress it up in fancy legal language or tell me that your copyright lawyer or court of appeal has absolutely no problem with it, but at the end of the day, AI companies simple took everything they could legally and illegally scrape from the Internet, Wikipedia, pirated book sites, image libraries, in order to build their AI models. They didn’t ask permission; in the now well-established manner established by Google, Facebook, and their ilk, they simply “moved fast and broke things”. Did Facebook ask me whether they could use the Turkish edition of my What Would Marx Do? that they found in the pirate site LibGen to train their Large Language Model? They did not!

Anyway, I don’t want to get into all of that here, as it’s been exhaustively covered elsewhere, but also because it’s just one of the problems AI raises. So, Problem 4 is “the Climate”. Again, I won’t go into this in detail (you can wade through it yourself, if you want), but let’s just say that AI is not lessening the climate crisis. It may do at some point (and I can’t deny that possibility – in fact, would welcome it), but it’s difficult to justify the environmental impact of data centres with the Ghiblification of social media profiles, filling Amazon with poor quality AI-created books, or its many other frivolous and dubious uses.

Problem 5 is its impact on employment and careers. Giddy with the prospect of reducing staffing and production costs, many employers (publishers included) are enthusiastically embracing AI. But aside from the shortsightedness of said employers regarding the social impact of this strategy (who’s going to buy your goods and services when no one has a job?), AI output is often of worse quality than the employees they are replacing. But whether it’s six fingers, logical fallacies, unsafe advice or unchecked bigotry – again, I’m sure you’re aware of all of these AI faux pas – we’re far from the point where AIs can outperform humans across all fields in a reliable, value-adding sort of way.

Problem 6 is the ensloppification of the Internet. There once was an indie rock band called Pop Will Eat Itself, and I think they had a point. We can apply the same logic to AI. It’s a circularity that Descartes himself would have been proud of: AI is trained on the Internet; people use AI to publish to the Internet; AI is trained on AI produced products… It doesn’t take a genius to see that there are diminishing returns in this process, and that the very thing that is needed to keep the AI product “healthy” – fresh human content – is the very thing that AI is eradicating by destroying the ability of creatives to make a living.

Problem 7 is homogenisation. You can often spot an AI generated image a mile off. One of the effects of AI language and image models seems to be to create a certain standard “look” or “tone”. This is a consequence of the training process, where patterns are identified and built upon, but it may also be – as tech critic Jaron Lanier has pointed out – the way that software systems work in general. You sign up to this fresh new thing called “Facebook”, and at first everything is exciting and cool. So that’s what happened to your bully from school! (He’s a tech entrepreneur.) But as the platform grows, it becomes more and more inflexible, locking in arbitrary decisions that were taken early on in the design process and now can’t be changed – whether they are beneficial or not:

Digital structures tend to have an all or nothing quality, just like a digital bit. A design like Facebook will tend to either fall by the wayside or become a universal standard, and if it’s a universal standard, it becomes harder to unseat than a government.4

You might also call this “the tyranny of success”. When AI is so ubiquitous that everyone is using it, then everything produced will have that AI “flavour” as standard.

Well, I don’t know if I speak for you, dear reader, but in response to that, all I can say is, “Bleurgh”.

There are probably more problems than those I’ve listed above, but I think they’re the main ones. I promised that I would come back to that word “customisation”, as I think it sums up a lot of what’s wrong with AI: it treats the user as a customer. It is often designed to flatter or please, and so tells the user what it wants to hear: “What an insightful question!”, “You’ve hit the nail on the head”!, and so on. But as the word itself suggests, the bottom line in all this is a financial one. Whatever purpose you use AI to serve, its primary justification is almost always that it will do it quicker and more cheaply. However, most of the time, it is not doing it better than a human could.

This is especially true when it comes to creativity, for what even does “better” mean here? If we take the purpose of literature, music or art as to give insight into the human condition, to connect emotionally with its audience, then machines can only simulate that, because (a) they are not human, and (b) they do not have emotions. They are not mortal. They do not love. They do not have bodies. I could go on, but hopefully you get the point. A machine possesses no properties that make it a subject of experience. Could you learn something from what AI has written or created? Of course, but only because it’s copying and remixing human creativity. And let’s remember, I can learn all sorts from insentient things: watching a water droplet evaporate can teach me about mortality and identity. Doesn’t mean the water droplet deserves human rights.

I could spend more time debunking AI myths, but that’s for another post. Instead, I’ll finish here by outlining what I think the AI policy should be for WoodPig Press in light of the above problems. Let’s do a quick recap:

- AI gets things wrong

- AI is damaging education and culture

- AI is based on theft

- AI is harming the environment

- AI is destroying careers

- AI is ruining the Internet

- AI is leading to homogenisation

OK, now the main question is that, given the above issues, is it legitimate for us to use AI for anything at all? Well, what uses could it have for WoodPig Press?

- Use in publishing books, and the publishing services that we provide.

- Use by authors and clients.

- Creation of text and images for the website, social media, newsletters, etc.

I think that’s more or less it. Let’s take these in order.

If we use AI to edit, design or illustrate the works we publish, or those titles we work on for indie authors and publishers, then we would be complicit in most of the problems I’ve outlined. It would be hypocritical to moan about job loss, and then do something that contributed to that. So, it seems a straightforward policy to say:

“Neither WoodPig Press nor any of its freelancers will use generative AI to design, illustrate, edit or proofread works published direct through the press, or those titles worked on for clients.”

OK, what about number 2? First of all, the above answer applies equally to authors and clients: if we don’t use AI, then neither should we be happy to work with authors or clients who do. But use in what sense? Well, this is a greyer and more controversial area.

First of all, there is its use for research and writing. Internet search is now increasingly AI driven. Aside from those little summaries that now appear at the top of most search results, AI is used to better understand the search query, to rank results, to personalise responses, etc. Add to that the problem that a growing number of web sources in those results may have used AI to generate their content in the first place, then it basically seems impossible to use internet search without also using AI. And this may become true of other software as well – even spelling and grammar checkers (some of which now use AI). So, it may be impossible to exclude AI use from tasks that were once more simply “automated”.

In order to make any principled stance meaningful, we therefore need to distinguish between generative AI and assistive AI. The use of AI in internet searches, spelling and grammar checkers, etc, is assistive, in that it is not a tool of creation, but a tool that aids you in your activities, like the timer on your cooker, or the beepy thing in your car that tells you that you’ve forgotten to put your seatbelt on. So, you get little squiggly red lines under your misspelt words, and maybe a suggestion or two about word choice or subject-verb agreement, but the software is not responding to a prompt to create or heavily revise material. Similarly, in illustration terms, Photoshop might use AI to better apply a filter effect on a certain layer, but it’s not being told “paint me a moonlit sea in the style of Van Gogh”.

But what if you use AI for fact checking, brainstorming ideas, or to directly query it regarding some topic? As I’ve said earlier, I do believe AI agents are the future of internet search – maybe even (properly thought through and restricted) aspects of education. If we can overcome the underlying problems (accuracy, copyright theft, joblessness, environmental impact, etc), then I would have no problem using it to explore a topic or to check facts. Brainstorming, less so, because for me this is part of the creative process, and if you start outsourcing your eureka moments to AI, then I can’t see it making your work better (at least, not in a way in which you could still call it “yours”). Should we disbar authors or clients who use it for brainstorming? Well, I guess you can’t – and ideas can come from anywhere, so maybe it’s just a question of how apt that idea is, or how well you go on to execute it. Regarding fact checking and exploring topics, then the current issue is accuracy, so that would be a worry. The solution for us perhaps is transparency. I wouldn’t want to publish someone who had only used AI to research their non-fiction book. However, I would class all of these uses as assistive rather than generative, and therefore – subject to transparency regarding how and to what extent it was used – allowable.

Our next policy is therefore:

“We will not publish or work with authors or clients who use AI for generative rather than assistive purposes.”

OK, and finally, number 3: should we be allowed to use AI for general website, social media, and other duties? Well, for social media text – where for me the point is to connect with people by not sounding like a corporate robot – there would be no point, and obviously we wouldn’t use it for images. And the same goes for the website and newsletters.

I think perhaps there are a small number of possible exceptions to this. The first would be website code. I mean, if an AI can generate CSS to help images display properly on a web page, then I don’t feel particularly guilty about that, because computer programmers have made a living out of automating people out of work since they began! I’ve experimented with this a little, and it can work (with some trial and error), so if the general ethical and other issues weren’t issues, then I’d probably do this. The same goes for policy documents (e.g. GDPR compliance, privacy and data, cookies), which no one really wants to write or read, and very possibly for legal agreements and contracts – would I feel guilty about putting a lawyer out of business? Given that a lot of legal stuff is template driven, in the use of stock phrases and terms, then a lawyer’s worth lies less in the act of creation and more about technical knowledge. However, aside from the fact that I have no great love for contract law, the main obstacle that would prevent me from using AI here is the worry that it was wrong in some important (and legally perilous) respect – as I would with AI medical advice! But again, it may be impossible to rule out that AI has been used in the development of any templates, contracts or policies that I adapt or get some lawyer to write for me. So, I think it’s probably simplest just to say:

“Aside from from templates for boring or technical stuff (which no one reads, and we may not know who wrote it), we do not use generative AI to create text or images for social media or the substantive pages and posts on this website.”

Not quite as succinct, perhaps, but honest.

So there you have it. As I say, there are some uses that I would happily use AI for, where it doesn’t put others out of meaningful work, and doesn’t impact on human creativity and intellectual development. But even here there is the environmental question. And in this, of course, AI is not the only contributor. The Internet itself is a chief culprit. So, we’re all compromised, in that sense. This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be concerned about the environmental impact of AI – we absolutely should. But we need to balance it with its advantages, and the comparable impact of the other frivolous, unethical things that we routinely turn a blind eye to (tin mining for smartphones and electric car batteries, anyone?).

But you have to pick your battles; you can’t fight them all at once. And for me, the chief battleground as a writer, illustrator, book designer, and publisher, is the preservation of human creative activity.

Are you on board with that?

- Just to reassure you, I have conducted absolutely no opinion-finding research for the purposes of this post. ↩︎

- Understanding Media (1964). NOTE: all the quotes in the post were sourced via ChatGPT, so don’t blame me if they’re wrong. ↩︎

- And since Edison ALLEGEDLY took credit for a lot of things he didn’t invent, maybe this inspiration was an even smaller percentage than he claimed. ↩︎

- https://www.jaronlanier.com/gadgetcurrency.html ↩︎